A HAPPENING IN RED SQUARE

The many people moving through Red Square at day’s end were thinking ordinary thoughts. Workers on their way home fretted over family matters. Shoppers plotted purchases or congratulated themselves on what they’d found to buy or lamented what they hadn’t. Tourists waited patiently in the line outside Lenin’s crypt. Plainclothesmen of the KGB watched the crowds for signs of unusual behavior that might suggest unorthodox ideas and found none.

The many people moving through Red Square at day’s end were thinking ordinary thoughts. Workers on their way home fretted over family matters. Shoppers plotted purchases or congratulated themselves on what they’d found to buy or lamented what they hadn’t. Tourists waited patiently in the line outside Lenin’s crypt. Plainclothesmen of the KGB watched the crowds for signs of unusual behavior that might suggest unorthodox ideas and found none.

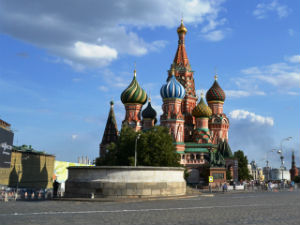

No one in the streams of pedestrians hurrying past the Kremlin and the Mausoleum, GUM store and St. Basil’s colorful spires on that March 31, 1980, imagined that something was about to happen that would affect all their lives They did not think much about great events because such doings, in fact doings of all sizes and weights, were out of their hands, decided in obscure places at dizzying heights. Whatever would come would come, and as always they would be swept along.

So it has always been with the Russian people. Our long past can be summed up in one phrase: not happy. What nation’s history can match ours in tyranny, conquest by brutal outsiders, pulverizing oppression? The Mongol marauders stayed for two and a half centuries. At last in 1917 came the nobodies’ day to “make their own history”— and then what? More misery, civil war, famine, “liquidation,” war again.

When things eased up again the people were very quiet. Once again their history was being made by others over their heads and out of sight.

No wonder those making their way through the square this day at dusk were not mulling over their long history of pageantry and carnage. Somebody else was always in charge of such large and stirring matters. Ordinary people had better be concerned with ordinary problems, like how one qualifies for an official rest-cure.

Among those traversing the square this gray, chilly Moscow eve was Ivan Nikolaevich Petrov, a factory worker. For him, too, it was a day like any other. He had his job, his family, and — soon to start up again — his soccer-Saturdays. In each department of his life he could honestly say that, if he was not altogether satisfied, neither did he have grounds for a true complaint.

After all, what can a man ask? So long as you do your work your needs are more or less provided for, right? Like the time he fell down the steps at the factory and damaged his leg— didn’t the doctors fix it? Sure he was left with a bit of a limp, and sure it hurt when he tried to play soccer, which meant he had to give up soccer. Yet in a capitalist country, so he’d read, he’d have needed more money than any worker had to pay the clinic and he might have lost his job. Yes, in the balance he was lucky to be a “Soviet man.”

All in all Ivan was a man at peace with his environment. He even had a way to deal with the assembly line at the “Vanguard” plant. When the repetitive movements of his hands began to dim his neglected brain he just focused his thoughts on a recent soccer game, recreating it play by play. By Thursday even that didn’t help, but Friday was better because he had the weekend’s relief within grasp. And during the soccer season Saturday was the joy of his life because he could watch his son Andrei in action. . . .

So life was good enough. Besides, he lived by this motto: A Soviet man should not complain! He after all had something to look forward to. The shining future. Communism! Let’s not be afraid to say it — Perfection. Whether he lived to see it or not. It’s coming, that’s the point. Sooner or later.

If he were a complainer . . . but where would you go to complain about the death of a wife while still young? Not the Supreme Soviet, not anywhere. He’d been left with a deep pain, then a void. His decision was not to marry again. Bad luck a man had to live with. Besides, he had Andrei and Tanya to raise. How could he have managed without Nina Georgievna? His mother-in-law had without a moment of hesitation stepped in to help with the children and run as much of a home as they had, their portion of an apartment shared with two other families.

That apartment bursting at the seams. There was something to complain about, but it would be a waste of breath. Once he’d thought of moving to another city where there wasn’t such a shortage of living quarters. But to get a residence you needed a work certificate, and to get work you needed a residence certificate — in other words, forget it.

No, better to accept your life as it is. Sure, his could be improved — but the Party told him it was improving, and had the statistics to prove it. In any case it was good enough for now.

So thought Ivan Nikolaevich Petrov, a man at peace with his environment. But something was about to happen on Red Square that would have a strangely unsettling effect.

If he’d turned left after passing GUM he might not have seen it at all. But he walked toward the front of St. Basil’s, precisely the scene of this most unusual event.

In front of the cathedral three young people, two men and a woman, had taken a position facing the Kremlin. Now, suddenly, just as Ivan drew close, one of them took from under his coat a rolled canvas and handed its end to the others, who pulled at it until it was unfurled. All three tugged at the sheet to draw it taut.

In front of the cathedral three young people, two men and a woman, had taken a position facing the Kremlin. Now, suddenly, just as Ivan drew close, one of them took from under his coat a rolled canvas and handed its end to the others, who pulled at it until it was unfurled. All three tugged at the sheet to draw it taut.

The banner carried these hand-painted words:

RESPECT THE SOVIET CONSTITUTION

Ivan could hardly apprehend the situation. He had never in all his life seen such a thing except in television reports of civil disturbances in far-off countries such as the United States.

He stopped to stare, as did some other passersby. In less than a minute half a dozen burly men were running up — druzhinniki, members of the KGB civilian auxiliary, Ivan guessed. They were yelling, “Parasites! Yids! Anti-Soviets!” Some of them grabbed at the banner but it took some time to wrestle it away. The demonstrators kept shouting, “Who are you? By what authority do you interfere?” The young woman demanded, “Are you against the Soviet Constitution? What right do you have?”

Some onlookers, getting into the spirit of the occasion, began to exclaim at the demonstrators: “Who do you think you are! Go to work like everybody else! We’ll put you to work all right!” and so on. The insults got louder when one of the young men had his hat knocked off, releasing long hair that fell to his shoulders.

These protestors would not fight back. All they did was try to keep their grips on the banner for as long as they could. As soon as police reinforcements arrived the three were thrust into cars and driven away.

The spectacle was over. It had all happened so fast that the tourists lined up at the Mausoleum across the square never knew that anything was wrong.

The man next to Ivan was saying, “A scandal! A disgrace! Punk parasites like that slandering everything their elders sacrificed for!”

Ivan replied, “You have a point. They should show respect for the law. With foreigners here.”

“They should be put to hard labor, the hardest! No more living off honest people’s sweat! They must be ‘intellectuals.’”

“Still, comrade. Those words on their banner. Of and by themselves they were all right, wouldn’t you say?”

“Fooey! Nothing but a counterrevolutionary provocation! Do we need them to get respect for our Constitution? They’re just trying to make us think it’s not respected!”

But Ivan, being a man of some curiosity, was not satisfied. “But why? They must have some purpose. Why do such a thing, and get arrested?”

“How should I know? Don’t worry about it, comrade, it’s all in the hands of the authorities. They’ll get to the bottom of this. Good-bye.” The man made a farewell gesture and walked away.

Yes, Ivan thought, it’s not for people like me to worry about. The authorities have their job, I have mine. I build socialism, they protect it. They don’t come into the “vanguard” plant and take over my work and I don’t meddle in theirs. No, leave State matters to the State. It knows how to protect us from wreckers and malcontents.

The small crowd was drifting away. Only a couple of knots of people remained, talking animatedly about this inexplicable happening. And now three men in long dark coats came along to order even them on their way. Within minutes Red Square had returned to routine activity. Shoppers passed in and out of GUM, sightseers inched toward Lenin’s waxy remains, pedestrians hurried along thinking their usual thoughts.

Behind the Kremlin’s red walls those elevated ones in charge of such things continued to plot the destinies of 260 million ordinary souls. The intervention of three individuals, momentary, flimsy, into the placid flow of Soviet reality was over without leaving a-visible-trace.

Behind the Kremlin’s red walls those elevated ones in charge of such things continued to plot the destinies of 260 million ordinary souls. The intervention of three individuals, momentary, flimsy, into the placid flow of Soviet reality was over without leaving a-visible-trace.

In the metro, speeding home, the factory worker Ivan Petrov continued to puzzle over the event he could make no sense of. He decided to say nothing about it to his family. They would pester him to give the details over and over but they would not have the answer to the question that rose and fell in his head as his hands rose and fell over the assembly line. What was so wrong with saying to the world in big black letters, RESPECT THE SOVIET CONSTITUTION . . . ?